The 1955 Panther Model 65: Britain's Last Great Single-Cylinder Tourer

A Deep Dive into Yorkshire's Unsung Workhorse

In the landscape of 1955 Britain, a nation steadily rebuilding its identity and economy from the ashes of war, the motorcycle was more than a machine of leisure; it was the lifeblood of personal transport. For the working man, the daily commute was not a recreational jaunt but a necessity, and the ideal vehicle was one defined by reliability, economy, and robust simplicity. It is from this crucible of post-war austerity that the 1955 Panther Model 65 emerges, not with the roar of a racer, but with the steady, dependable pulse of a true British workhorse.

When one thinks of the Panther marque, the mind invariably conjures the image of a colossal single-cylinder engine, canted forward at a dramatic 40-degree angle, serving as a stressed member of the frame. These heavyweight "slopers," like the legendary Model 100, were machines of immense character and torque, renowned for their ability to haul a sidecar with an unhurried, "firing once every lamp-post" rhythm. Yet, the Model 65 stands apart from this iconic lineage. It is a different kind of Panther, one born from market pragmatism rather than the company's signature, radical design philosophy.

The existence of the Model 65 and its lightweight brethren signifies a crucial strategic pivot by its maker, Phelon & Moore (P&M). It was a move away from their established identity as builders of large, unconventional sidecar tugs to compete in the fiercely contested post-war commuter market. The company's core identity was forged around the patented sloping, stressed-member engine, a concept that had defined them since their earliest days. This was their unique engineering statement to the world. However, the post-war environment demanded cheap, efficient transport, a segment dominated by giants like BSA and Triumph. P&M's response was not to simply scale down their famous sloper design, but to create an entirely new line of lightweights with conventional vertical engines and traditional tubular frames, which debuted for the 1949 model year. This decision was a pragmatic, if perhaps reluctant, admission that their signature design was not suited for the new market reality.

In this context, the Model 65's conventional design was, paradoxically, a radical step for the proudly individualistic Yorkshire firm. The 1955 Panther Model 65, with its refined swinging-arm frame and dependable 250cc engine, represents a pivotal moment for the company and stands today as an often-overlooked gem for the discerning classic British motorcycle enthusiast.

The Phelon & Moore Legacy: From Yorkshire Pioneers to Post-War Pragmatists

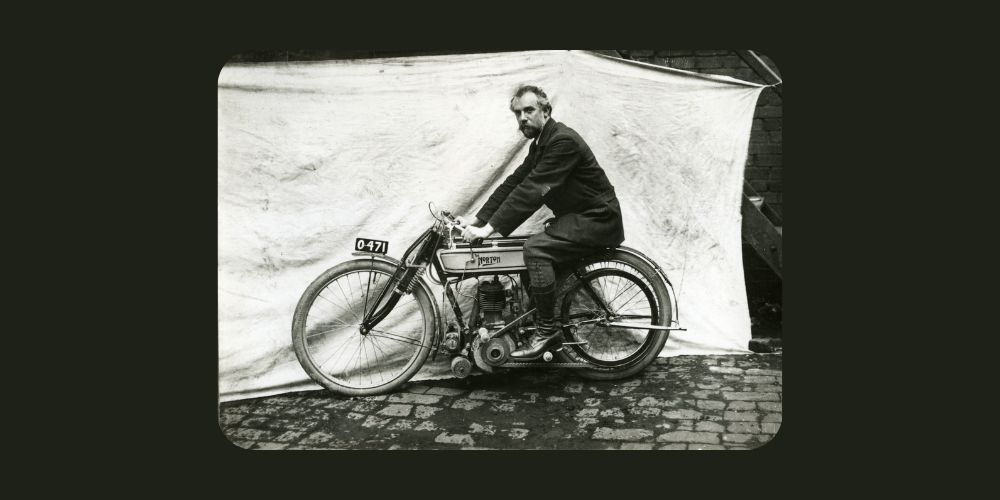

To understand the Model 65, one must first appreciate the rich and innovative history of the company that built it. Phelon & Moore was established in 1904 in the industrial heartland of Cleckheaton, Yorkshire, by the pioneering duo of Joah Phelon and Richard Moore. From its inception, the firm was a hotbed of engineering innovation. The foundational concept of the sloping engine as a stressed frame member was patented by Phelon and his nephew Harry Rayner as early as 1901. This design was not merely an aesthetic choice; it reduced weight and simplified frame construction, a truly forward-thinking idea. P&M followed this by producing the first completely chain-driven motorcycle in 1905, a machine that also featured a two-speed gear system, setting a new standard for drivetrain technology at a time when many competitors still relied on leather belts.

Throughout the early 20th century, P&M built a formidable reputation for producing solid, well-constructed, and reliable machines, marketed under the slogan "The Perfected Motorcycle". Their quality was proven in the toughest arenas of the day, with P&M motorcycles competing in the very first International Six Days Trial (ISDT) in 1913 and earning accolades for their endurance. This reputation for toughness led to significant military contracts; during the First World War, the Royal Flying Corps used P&M motorcycles extensively, keeping the Cleckheaton factory busy throughout the conflict.

However, P&M's history is also marked by a recurring pattern of brilliant engineering that did not always translate to commercial success. This suggests a company culture that often prioritized engineering ideals over market trends, a characteristic that both defined their unique legacy and contributed to their eventual demise. For instance, in the early 1930s, the company commissioned the famed designer Granville Bradshaw to create the "Panthette," a technically advanced 250cc transverse V-twin. While it received glowing reviews from test riders, it was a commercial disaster, and its failure to sell, coinciding with the Great Depression, nearly bankrupted the firm.

Decades later, in the late 1950s, P&M's attempt to enter the booming scooter market with their own "Panther Princess" was another costly failure that helped bring about the end of the company.

It was against this backdrop of pioneering spirit and hard-learned commercial lessons that the post-war lightweight range was conceived. After World War II, Britain was economically challenged, and the demand was for affordable, utilitarian transport. P&M's response was the Model 65 and its 350cc sibling, the Model 75. These were designed explicitly as "modest commuting bike[s] for the working man coming home from the war into austerity Britain".

In a significant departure from their heritage, these new models utilized a conventional tubular frame and an upright engine, a design first adopted for their roadsters in 1949. The Model 65, therefore, was not just another motorcycle; it was a symbol of P&M's adaptation and survival—a pragmatic machine born from the necessity of a changing world.

Anatomy of a Classic: The 1955 Panther Model 65 in Detail

The 1955 model year represents a point of significant refinement for the Panther Model 65, marking it as a particularly desirable iteration for collectors and riders today. It benefits from a series of crucial upgrades implemented in the years following its 1949 debut, creating a more modern and capable machine. This evolution can be traced through several key developments that culminated in the 1955 specification.

A Modern Chassis: The Swinging-Arm Evolution

The single most important development in the lightweight Panther's history was the introduction of a pivoted fork, or swinging-arm, rear frame for the 1953 model year. This fundamentally transformed the motorcycle's character. The original 1949-1952 models were built on a rigid frame, offering a ride characteristic of an earlier era—direct and connected to the road, but often harsh and unforgiving on Britain's less-than-perfect post-war surfaces. The move to a swinging-arm rear suspension, controlled by a pair of shock absorbers, was a massive technological leap forward, providing vastly improved rider comfort and more predictable handling, especially over uneven ground.

The suspension system saw further refinement in 1954. Early post-war Panthers, including the first lightweight models, were fitted with innovative Dowty Oleomatic "air" forks. While advanced for their time, P&M transitioned to their own, more conventional oil-damped telescopic forks in 1954, which became standard on the 1955 model.

This move created a more cohesive and familiar chassis package. The final piece of this chassis evolution came in 1955 with the introduction of new alloy wheel hubs, which replaced the previous 6-inch half-width steel hubs. This was a subtle but important upgrade, reducing unsprung weight and further modernizing the motorcycle's specification. Consequently, the 1955 Model 65 represents a "sweet spot" in the model's development, incorporating all the major post-launch improvements into one refined and highly usable package.

The Heart of the Matter: The 248cc Engine

At the core of the Model 65 is its 248cc (commonly marketed as a 250cc) single-cylinder, overhead valve (OHV) engine. Unlike the famous slopers, this unit featured an upright cylinder, housed within a conventional tubular cradle frame. The engine's design, with a bore of 60mm and a long stroke of 88mm, prioritized torque and reliability over high-revving power.

Despite its conventional layout, the engine retained a unique Panther design trait: the dry-sump oil tank was ingeniously incorporated into the main engine crankcase casting. This clever piece of packaging, a carry-over from their sloper models, eliminated the need for a separate, frame-mounted oil tank, contributing to the bike's clean and uncluttered lines under the saddle. Another unusual technical feature for the era was the use of plain bush main bearings for the crankshaft, a testament to the robust, no-frills engineering philosophy of the Cleckheaton factory.

Drivetrain, Electrics, and Finish

Power was transmitted through a Burman gearbox. While some sources suggest a three-speed unit was standard on the base model, a four-speed gearbox was a key feature of the "de luxe" variant and appears on later models. An auction listing for a 1953 Model 65 Deluxe explicitly notes a four-speed manual transmission, suggesting this was the premium option available by the mid-1950s.

A key technical differentiator between the Model 65 and its larger 350cc Model 75 sibling was the electrical system. While the Model 75 utilized a Lucas K1F magneto for ignition, the Model 65 was equipped with a simpler and more common points and coil system.

The motorcycle's appearance was understated yet handsome. A 1951 sales catalogue describes the standard finish as a royal blue petrol tank with eggshell blue panels, elegantly lined in gold. This was complemented by a nicely profiled saddle tank that gave the bike a modern look for its time. The overall impression was one of quality and solidity, a machine built to last.

Technical Specifications of the 1955 Panther Model 65

Compiling a definitive list of specifications for any classic motorcycle can be a challenge, and the Panther Model 65 is no exception. Data is often scattered across period brochures, workshop manuals, and modern analyses. The following table synthesizes the available information to provide a comprehensive technical overview of the 1955 Panther Model 65, focusing on the refined swinging-arm model of that year. This serves as a valuable quick-reference guide for enthusiasts, restorers, and potential owners.

| Specification | Details |

|---|---|

| Engine Type | Single-cylinder, 4-stroke, Overhead Valve (OHV) |

| Displacement | 248cc (marketed as 250cc) |

| Bore x Stroke | 60mm x 88mm (long-stroke design) |

| Power Output | Approximately 10.4 bhp @ 5,000 rpm |

| Lubrication | Dry sump with oil tank integrated into engine crankcase |

| Ignition | Points and coil system |

| Gearbox | Burman 4-speed (likely standard on de luxe models by 1955) |

| Frame | Conventional tubular cradle, swinging-arm rear |

| Front Suspension | Phelon & Moore oil-damped telescopic forks |

| Rear Suspension | Swinging arm with twin shock absorbers |

| Brakes | 6-inch drum (front), 6.5-inch drum (rear) |

| Wheels | Spoked with alloy hubs |

| Tires | 26" x 3.25" (front and rear) |

| Wheelbase | 54 inches (1,372 mm) |

| Dry Weight | Approximately 304 lbs (138 kg) |

On the Road: Performance, Handling, and the Riding Experience

The Panther Model 65 has, over the years, acquired a reputation for being somewhat "underpowered". With a claimed output of just 10.4 bhp, it is certainly not a machine built for high performance. One period assessment even described it as being in "strictly 40mph territory". However, to judge the motorcycle solely on its power output is to misunderstand its purpose and its context.

The performance critique is largely a modern or comparative one. The Model 65 was explicitly designed as an economical commuter for austerity Britain, a role in which outright speed was secondary to fuel efficiency and reliability. Its predecessor, the Model 60, was lauded for achieving over 100 miles per gallon, a highly valued characteristic that was likely inherited by the Model 65. The fact that Phelon & Moore kept the model in production for over a decade, from 1949 until the early 1960s, indicates that it was commercially successful and fulfilled its market role effectively. For its intended rider in 1955, the performance was likely considered perfectly adequate, and its low running costs were a significant advantage.

Where the 1955 model truly shines is in its ride and handling. The combination of the swinging-arm frame and P&M's own telescopic forks provided a level of comfort and stability that was a world away from the harshness of earlier rigid-framed machines. This well-sorted chassis, combined with its relatively light weight of around 304 lbs, made it a nimble and pleasant machine for navigating the country lanes and B-roads for which it was designed. A sales listing for a similar 1957 model notes that it "pulls strongly for a 250" and is "perfect for a sunny run around the lanes or club runs," a sentiment that captures the bike's true character.

For the classic enthusiast today, the Model 65 offers an exceptionally usable and unintimidating entry into the world of British motorcycling. Its modest power is non-threatening, its simple mechanics are easy to understand and maintain, and its light weight makes it easy to handle at low speeds. It is a motorcycle that encourages a relaxed pace, allowing the rider to enjoy the journey rather than rushing to the destination.

Owning a Panther Model 65 Today: A Guide for Collectors and Restorers

For those considering adding a piece of Yorkshire's finest engineering to their garage, the Panther Model 65 presents a uniquely compelling case. It combines historical significance with accessibility, both in terms of market value and mechanical simplicity.

Market Value and Collectibility

The Panther Model 65 remains one of the more affordable entry points into post-war British classic ownership. Recent auction results show a wide range, heavily dependent on condition. A 1955 250cc model sold for a respectable £1,725 (approximately $2,348) in 2021, while another example sold for just £575 back in 2013. Project bikes requiring full restoration typically sell for around the £1,000 mark. At the other end of the spectrum, fully restored and road-ready examples are often advertised for over £3,000. Valuation guides, such as Hagerty's, place the value of a 1955 model in good condition at around $2,600, confirming its status as an accessible classic.

The Owner's Community: A Crucial Asset

Perhaps the single greatest advantage of owning any Panther is the exceptional support network provided by the Panther Owners Club (POC). Mentioned repeatedly as an essential resource, the POC offers its worldwide membership technical assistance, a comprehensive spares scheme, and a vibrant community of fellow enthusiasts. For a relatively rare marque, this level of organized support is invaluable and transforms the ownership experience from a potentially frustrating hunt for parts and knowledge into a rewarding journey backed by a wealth of expertise.

The combination of the Model 65's relatively low market value and the extraordinary strength of the owner's club creates a unique and highly attractive proposition. Aspiring classic owners can acquire a genuinely historic and interesting British motorcycle without a massive financial outlay, while simultaneously gaining access to the kind of premium support network typically associated with much more expensive "blue-chip" classics like Vincents or Brough Superiors.

Restoration and Maintenance

The Model 65's straightforward design makes it an excellent candidate for the home restorer. Its simple single-cylinder engine and basic electrical system are far less complex than many of its multi-cylinder contemporaries. A wealth of documentation is available to assist in this process, including illustrated spare parts manuals and workshop instruction books, many of which have been reproduced and are readily available.

Like many classic British bikes, Panthers have their quirks. The heavyweight models are notoriously heavy on oil consumption, a trait that may be shared to some degree by the lightweights. However, the strong owner's community has developed solutions over the decades. For example, owners of the larger Model 100 have successfully adapted modern Volvo car pistons to improve oil control, a testament to the creative and practical approach within the Panther community. Parts, both used originals and newly manufactured reproductions, are available through the club and specialist suppliers, ensuring that keeping these machines on the road is a feasible and rewarding endeavor.

he Enduring Appeal of a Yorkshire Classic

In the grand chronicle of British motorcycling, the 1955 Panther Model 65 does not command the same headline attention as a Bonneville, a Gold Star, or even its own stablemate, the mighty Model 100. It is a quieter, more modest machine, but its significance is no less profound. It represents a vital chapter in the Phelon & Moore story—the pragmatic and well-built motorcycle that helped the company navigate the challenging economic currents of the post-war era.

The Model 65 is the unsung hero of the British motorcycle industry: the dependable, economical commuter that kept the country moving. It embodies the robust engineering heritage of its Yorkshire creators, refined with the modern comforts of a swinging-arm frame and telescopic forks. Its performance is modest, but its reliability and simplicity are its greatest virtues.

Today, the enduring appeal of the 1955 Panther Model 65 lies in its honesty. It offers a direct, unfiltered connection to a bygone era of British motoring, free from pretense. For the enthusiast seeking a usable, charming, and affordable classic with an unparalleled support network, this often-overlooked Panther is not a forgotten footnote, but a perfect choice—a true piece of "perfected" motorcycling history from Cleckheaton.

Interesting Facts and Stories

Engineering Curiosities

The Sloper Design: Panther's forward-sloping cylinder wasn't just styling—it allowed the engine to sit lower in the frame, improving center of gravity and ground clearance simultaneously.

Cast Iron Cylinder: While many manufacturers switched to aluminum for weight savings, Panther stuck with cast iron—heavier, but better heat dissipation for sustained heavy loads.

Massive Flywheel: The Model 65's flywheel weighed nearly 20 pounds—contributing to that characteristic slow-revving smoothness and making the engine nearly impossible to stall.

Wartime Connection

During WWII, Phelon & Moore supplied motorcycles to British forces, though their 350cc models saw more military use than the big 600cc machines. Post-war, many servicemen familiar with Panthers bought civilian models—brand loyalty built through military service.

Celebrity Connections

Unverified but persistent legend: Author George Orwell supposedly owned a Panther with sidecar in the late 1940s, using it for countryside excursions from his Scottish retreat. No definitive proof exists, but the timeframe and Orwell's modest means make it plausible.

Record Attempts

Verified: In 1957, a modified Model 100 (650cc Panther) attempted speed records at Montlhéry circuit in France, achieving 90+ mph—impressive for a big single designed primarily for sidecar work.

The Last Big Single

The Model 65 holds distinction as one of the last large-displacement single-cylinder production motorcycles built in Britain. By the time production ceased in 1965, twins and multis had completely taken over. Forty years would pass before single-cylinder engines returned to fashion—and then only in much smaller displacements for lightweight adventure bikes.

Why the 1955 Model 65 Matters

The Panther Model 65 represents several things simultaneously:

Engineering Philosophy: It's the ultimate expression of "bigger is better" in single-cylinder design—prioritizing torque and reliability over speed and sophistication.

Social History: These motorcycles moved British families through the 1950s and 60s, providing affordable three-person transportation when cars remained out of reach.

End of an Era: The Model 65 was among the last big British singles, superseded by twins and eventually multi-cylinder machines. Its 1965 discontinuation marked the end of 60+ years of Panther production.

Collector Appeal: Rarity, historical significance, and sidecar capability make surviving Model 65s increasingly collectible. They're not investment-grade (yet), but prices have climbed steadily.

For enthusiasts willing to embrace 1950s technology, the Model 65 offers authentic vintage motorcycling. It's not fast, not sophisticated, and not particularly comfortable by modern standards. But it's honest, capable, and connects riders to an era when motorcycles were tools first, toys second.

The 1955 Panther Model 65 didn't change motorcycling—it represented the last gasp of an approach about to disappear. That makes it historically significant and, for those who appreciate anachronisms, deeply appealing.

Is the 1955 Panther Model 65 a good motorcycle for a beginner rider?

No. The Model 65's weight (420 lbs), hand-shift gearbox, rigid rear frame, and drum brakes make it challenging for new riders. Additionally, parts scarcity means mechanical problems could leave you stranded. Beginners should start with smaller, more modern motorcycles. The Model 65 is best suited for experienced riders comfortable with vintage British machinery.

Can you still find parts for a 1955 Panther Model 65?

Parts availability is mixed. Engine internals, many Lucas electrical components, and some chassis parts are still obtainable through specialists like Draganfly Motorcycles and Panther Owners Club members. However, specific items like Dowty Oleomatic fork seals are no longer manufactured, requiring creative solutions or custom fabrication. Expect restoration to require patience, networking with other owners, and occasional custom machining.

How much is a 1955 Panther Model 65 worth today?

Values vary significantly based on condition. As of 2024-2025, restored running examples typically sell for £8,000-£15,000 ($10,000-$19,000). Project bikes requiring full restoration might cost £2,000-£5,000 ($2,500-$6,300). Concours-level restorations command £18,000+ ($23,000+), particularly if accompanied by a period-correct sidecar. Rarity and sidecar capability make these appreciating classics, though they're not yet commanding premium prices like contemporary Vincents or Brough Superiors.

About the Author

William Flaiz, passionate about European motorcycle brands, shares his expertise and stories on RunMotorun.com. He offers detailed insights and reviews, aiming to educate both seasoned enthusiasts and newcomers. Flaiz combines personal experience with thorough research, welcoming visitors to explore the rich world of European motorcycles alongside him.