The Desmodromic Valve System: Engineering Genius or Expensive Obsession?

If you've ever talked motorcycles with a Ducati owner, chances are they've mentioned "desmo" valves with a mix of pride and slight anxiety. But what exactly makes this system so special—and why does it seem like every other manufacturer is perfectly happy without it?

Let's dig into one of motorcycling's most fascinating engineering quirks.

What Problem Was Desmo Trying to Solve?

Picture a typical valve spring setup like a screen door with a standard spring. You push the door open (that's your camshaft), and the spring slams it shut behind you. Works great for walking through. But now imagine you're trying to sprint in and out of that door hundreds of times per minute.

That's basically what happens in a high-revving engine.

Traditional valve springs have a problem at extreme RPM. As engine speeds climb past 10,000, 11,000, 12,000 rpm, those springs struggle to close the valves quickly enough. The valve might still be floating back down when the piston comes rushing back up. Bad news. Very bad news, actually—the kind that turns precision engine components into expensive confetti.

Engineers call this "valve float," and it's why most bikes have a redline in the first place.

Enter Fabio Taglioni's Solution

In the late 1950s, Ducati engineer Fabio Taglioni looked at this problem and thought: why use springs at all?

His desmodromic system—from the Greek desmos (controlled) and dromos (course)—uses a second set of lobes and rockers to mechanically close the valves instead of relying on springs. Think of it like having someone actively pulling the screen door shut instead of just letting the spring do it.

The valve opens. Then it's actively, positively closed. No floating. No guessing. Just mechanical certainty.

How It Actually Works

Here's where it gets interesting.

A conventional setup has one cam lobe that pushes the valve open. A spring pulls it closed. Simple. Reliable. Been working since the 1800s.

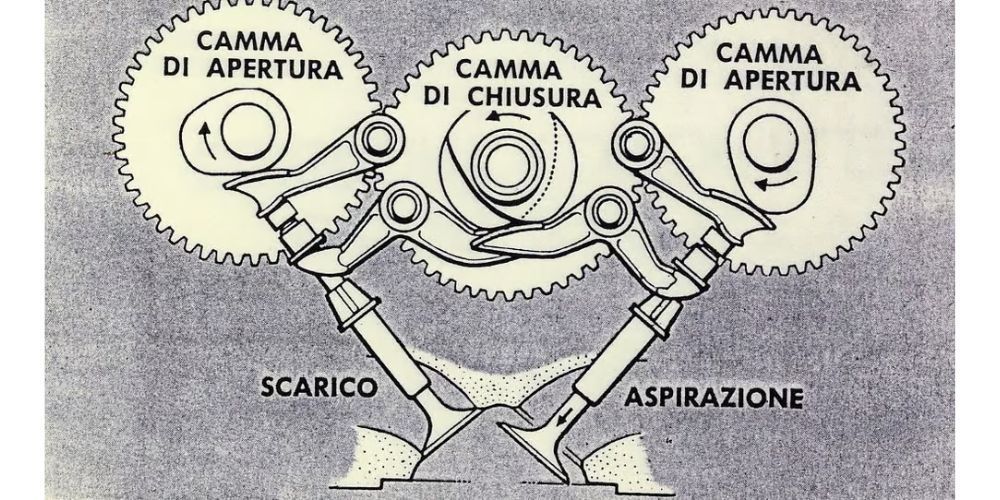

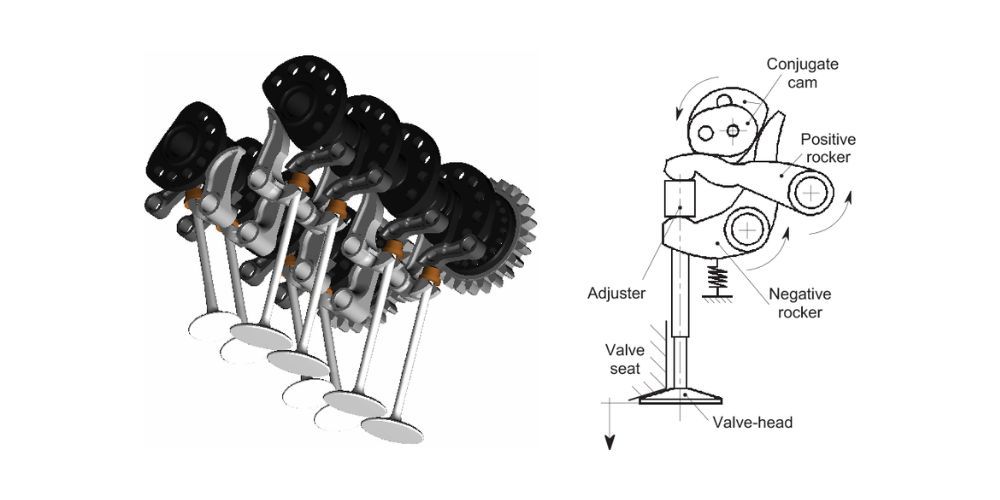

Desmo doubles down on the mechanical side. You've got:

- An opening rocker (pushes the valve open)

- A closing rocker (pulls it closed)

- Two cam lobes per valve doing this dance

- All of this happening thousands of times per minute

Imagine conducting an orchestra where every instrument needs two separate conductors—one to tell it when to play, another to tell it when to stop. That's the complexity we're talking about.

The Supposed Advantages

High RPM capability: Because you're mechanically controlling both opening and closing, valve float becomes nearly impossible. Ducatis can safely rev higher than equivalent spring-valve engines.

Reduced valve spring pressure: Without needing ultra-stiff springs to prevent float, there's less friction. Less friction means more power actually reaches the rear wheel instead of being eaten up by internal resistance.

Precise valve timing: At any RPM, the valve does exactly what the cam tells it to do. No spring harmonics, no weird behavior as the springs heat up and cool down.

That's the theory, anyway.

The Not-So-Fun Parts

Remember that screen door analogy? Now imagine that instead of one simple spring, you've got two separate mechanisms that both need to be adjusted perfectly. Not close. Not "pretty good." Perfect.

Desmo valve clearances need checking every 15,000-24,000 miles depending on the model. And "checking" is generous—more like "completely disassembling the top end of your engine to measure gaps between various rockers with feeler gauges."

This isn't an oil change. This is a multi-hour procedure that costs anywhere from $800 to $2,000 at a dealer. Some brave souls do it themselves, but you're looking at specialized tools and the constant worry that you've messed something up.

Miss a service? The tolerances get tighter as parts wear. Eventually, valves don't fully close. Your engine starts running like it has a permanent vacuum leak. Damage follows quickly.

Why Doesn't Everyone Use It?

Good question. If desmo is so brilliant, where is it on your Honda, Yamaha, or BMW?

Turns out, modern metallurgy and manufacturing have gotten really good. Titanium valves weigh almost nothing. Beehive springs and pneumatic valve systems (yes, air-operated valves) have eliminated most of the problems desmo was designed to solve.

BMW's S1000RR revs to 14,500 rpm with conventional springs and makes 205 horsepower. Yamaha's R1 with its crossplane crank hits 13,500 rpm all day long. Both use springs. Both work flawlessly with standard maintenance intervals.

The honest truth? Desmo made sense in 1958. In 2025, it's more about heritage than necessity.

The Real Reason Ducati Keeps It

Here's where it gets interesting from a business perspective.

Ducati knows their system is complex. They know it's expensive to maintain. They also know that every single desmo service drives customers back to Ducati dealers, creating a captive service market worth millions annually.

But there's something else—something harder to quantify. Desmo means something to Ducati owners. It's a badge of honor. A mechanical secret handshake. You don't just own a Ducati; you're part of a tradition that goes back to Taglioni's genius.

When Ducati released the Multistrada V4 in 2021, they broke with tradition. They used conventional springs. The engine required service intervals of 37,000 miles instead of 15,000. Owners loved it. But did it feel like a real Ducati?

That's the question the company is still wrestling with.

The Collector's Perspective

From a historical standpoint, desmo represents something important: Italian engineers refusing to accept limitations. While everyone else made springs stronger, Ducati eliminated them entirely.

Early desmo singles like the 1968 Mark 3D are genuinely remarkable pieces of engineering. The tolerances required to make the system work with 1960s manufacturing? That's craftsmanship bordering on art.

Modern classics—the 916, 998, 1098—will always command premium prices partly because of their desmo engines. These bikes represent the peak of Ducati's commitment to doing things their own way, market forces be damned.

Does It Actually Make the Bikes Better?

Let's be honest for a second.

The Panigale V4 makes 214 horsepower. It's one of the most potent production motorcycles ever built. The desmo system contributes to that, sure. But so does electronic fuel injection, ride-by-wire throttle, sophisticated engine management, and about a dozen other technologies that have nothing to do with valve actuation.

Could Ducati make the same power with springs? Probably. Would it feel the same? That's harder to answer.

There's an intangible quality to how desmo engines deliver power—a certain mechanical immediacy that enthusiasts swear by. Whether that's real or just good marketing and expectation bias is something I genuinely can't answer.

The Bottom Line

The desmodromic system is a solution to a problem that largely doesn't exist anymore. It's expensive. It's maintenance-intensive. It's completely unnecessary given modern technology.

And yet.

There's something undeniably cool about a system that treats engine operation as a purely mechanical problem. No relying on springs that might, possibly, under certain conditions, fail to do their job. Just cam lobes, rockers, and the absolute certainty that everything is exactly where it should be.

Is it rational? Not really. Is it Ducati? Absolutely.

If you're considering a Ducati, factor in the maintenance costs. Budget for those valve services. Maybe learn to do them yourself. And understand that you're buying into a philosophy as much as a motorcycle.

For some riders, that's worth every penny and every hour spent adjusting clearances. For others, it's an expensive anachronism that should've been retired decades ago.

The beauty of motorcycling is that both perspectives are completely valid. You get to choose which tribe you belong to.

How often do desmodromic valves need adjustment?

Depends on the model. Older bikes like the 916-998 generation needed service every 6,000-12,000 miles. Modern Ducatis with testastretta engines pushed that to 15,000-24,000 miles. The V4 Multistrada finally ditched desmo entirely for 37,000-mile intervals.

Can you convert a desmo engine to springs?

Theoretically, yes. Practically, no. You'd essentially be rebuilding the entire top end of the engine from scratch. By the time you're done, you've spent more money than just maintaining the desmo system—and you've probably destroyed the resale value of your bike.

Do desmo valves really make more power?

It's complicated. The system allows higher RPM without valve float, which can translate to more power. But modern spring systems are so good that the difference is negligible. Ducati's power advantage comes from overall engine design, not just the valve system.

About the Author

William Flaiz, passionate about European motorcycle brands, shares his expertise and stories on RunMotorun.com. He offers detailed insights and reviews, aiming to educate both seasoned enthusiasts and newcomers. Flaiz combines personal experience with thorough research, welcoming visitors to explore the rich world of European motorcycles alongside him.